Politicon.co

Ukraine’s deterrence by denial

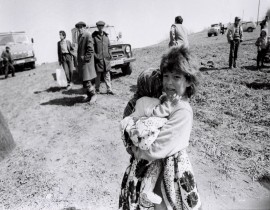

Photo by military journalist Taras Grenjpg-1599632067.jpg)

Anti-terrorist operation in Eastern Ukraine. Photo by military journalist Taras Gren

When Ukrainian President Viktor Yanukovych’s government was toppled by Euromaidan Revolution, Ukraine went through the most tumultuous part of its modern history. Right after its covert invasion to annex Ukraine’s Crimean Peninsula, Russia inflamed a separatist insurgency in Eastern Ukraine. As a response to growing chaos, Ukrainian government launched “Anti-Terrorist Operation” (also known as ATO) which was originally designed and carried out as a counter-insurgency operation.

Despite being unexpectedly feeble due to years of neglect of the military domain, Ukrainian forces (regular army and volunteer units) were initially mounting a string of successful offensives against pro-Russia separatists. This was enabled by relatively steady supply of military equipment and air superiority enjoyed by Ukrainian forces. During the early period of ATO, Ukrainian forces took control of key cities and towns previously held by separatists, including Sloviansk, Kramatorsk, Druzhivka, Kostyantynivka, and Artemiysk, among others.

One of the most alarming news for Russia was that Ukrainian forces were approaching border areas which were of immense importance for the separatists. Without access to border areas, they would have been unable to receive military supply and personnel from Russia to maintain fighting against Ukrainian forces. Seeing that its proxies are weaker in the face of consistent Ukrainian attacks, Russia began to transfer various types of military equipment, including advanced weapon systems to the separatists. For example, notorious Buk surface-to-air missile that was used to down a passenger aircraft (flight MH17) was transferred to its launch site from Russia. Another notorious instance was the Battle of Ilovaisk in which Ukrainian forces were encircled and forced to retreat under fire despite a previously-agreed humanitarian corridor. During the siege also known as “Ilovaisk tragedy” among Ukrainian public, Russian army units and hardware were noticed in mass quantities. Painful losses forced Ukraine to sign the Minsk agreement on September 5, 2014.

Fighting broke out again in early 2015 resulting in another round of losses for Ukraine. Notably, Ukrainian forces were suppressed in Donetsk Airport and Debaltseve. Specifically, the Battle of Debaltseve became a prime example of Russia’s role in the conflict when it was revealed that a tank brigade based in Siberia were dispatched to fight in Donbas. The winter campaign of the War in Donbas ended in the second Minsk agreement (February 12, 2015) which included clauses similar to the previous agreement in addition to conditions regarding withdrawal of heavy weapons. Although ceasefire is breached on a daily basis since then, violence across the frontline has not reached the same levels as witnessed in the “hot phases” of the war.

Deterrence: why and which?

Following Minsk II, Ukraine’s military posture in Donbas has been more of deterrent character rather than purely offensive or defensive one. The most important reason why deterrence is the optimal choice for Ukraine is related to power dynamics of the conflict’s participants. If we consider that the conflict in Eastern Ukraine is a “limited war” between Russia and Ukraine, then it becomes apparent that in military terms Ukraine is no match for Russia. Comparing military resources and capabilities of both countries reveals a clear-cut distinction of the weak and strong. Ukraine stands out as “a weaker part in asymmetric relationship, which is unable to change the nature of functioning of the relationship on its own.” Thus, like other small states, insufficient levels of military power in relation to its adversary made Ukraine to opt for deterrence as a strategy in Donbas. In other words, the role of military power in strategic calculations turns into a vehicle for stopping Russia’s further incursions into Ukraine while maintaining political pressure through international partners in order to achieve envisioned goals, such as re-integration of occupied parts of Donbas.

Since the reasoning behind why deterrence is explained, it is necessary to clarify which deterrence Ukraine utilizes in Donbas to maximize its security. Growing usage of the deterrence theory in strategic studies and military affairs prompted development of various classifications. Hence, several types of deterrence have been distinguished from one another on the basis of strategic approach (by denial and punishment), time period (general and immediate), scope (narrow and broad) and covered area (direct and extended).

As noted, in terms of strategic approach, deterrence can be achieved either by denial or by punishment. Deterrence by denial is similar to defense in practice and aims to proactively counteract enemy if it chooses to attack; whereas deterrence by punishment concerns building a force capability that would allow to inflict massive pain on adversary once it chooses to attack. In other words, deterrence by punishment discourages enemy from taking undesired actions, “because it fears the punishment that the deterrer will impose.” On the other hand, the purpose of deterrence by denial is to instill the idea that the enemy actions, such as armed attacks, “will be prohibitively costly and will not succeed because the deterrer is able to deny it the benefits it seeks.”

Moving from these concepts, deterrence by punishment becomes a choice that Ukraine would find desirable, but difficult to enforce due to lack of necessary means. However, deterrence by denial seems both in line with political situation, strategic documents and military capabilities of Ukraine. Among political commitments that Ukraine took by signing Minsk agreements are those that prohibit even small-scale attack. By breaching ceasefire, Ukraine at the very least would damage international support it enjoys and risk a new escalation. Key documents such as Military Doctrine of Ukraine (2015) and National Security Strategy of Ukraine (2015) identify building up a strong army as a way to guarantee restoration of Ukraine’s territorial integrity. While Ukraine cannot launch a large-scale attack against separatists in Donbas due to a high probability of overt Russian intervention akin to “hot phase” of the war in 2014 and 2015, it can use robust armed forces in order to discourage another wave of Russian aggression.

In the period that followed Crimea’s annexation and the eruption of the War in Donbas, Ukraine has undergone a substantial build-up of its military domain. As one expert accurately described, modern Ukrainian army is “a post-Soviet army in a high degree of combat readiness.” Ukrainian Armed Forces increased by almost 100,000 personnel and enlarged weapons inventory after debilitating battlefield losses of military equipment. Another signal regarding Ukraine’s espousal of deterrence by denial was its purchase of FGM-148 Javelin anti-tank missiles and launchers from the United States. Delayed during Barack Obama’s presidency, the sale was consequently approved by Donald Trump administration. Although Ukraine received non-lethal aid from United States until then, Javelin purchase was a big signal on U.S. willingness to support Ukraine militarily on defensive terms if large-scale hostilities erupt again.

Possible shift of strategy for future?

Although deterrence by denial seems to be the only enforceable option for the near future, Ukraine may change its strategic outlook if needed technologies will be acquired or mastered. This reasoning is substantiated by Ukraine’s purchase of Bayraktar TB2 drones from Turkey and its desire to overhaul Ukrainian Air Force until 2035. These moves, alongside Ukraine’s ongoing attempt to master indigenous production and modernization of short-range ballistic missile system “Hrim-2” (“Grom-2”), multiple rocket launcher “Vilkha-M” and anti-ship cruise missile R-360 “Neptune” manifest that acquisition of deterrence by punishment capability might be Ukraine’s long-term objective. In addition to naval targets, “Neptune” was also described by former Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council of Ukraine Olexandr Turchynov as a deterrent which can destroy the Crimean Bridge “in a few minutes.”

About the author:

Guntaj Mirzayev is a recent graduate from Masters programme in International Security Studies, jointly organized by Scuola Superiore Sant'Anna and University of Trento. Previously, he completed internships at the Center for Strategic Studies (Azerbaijan) and Razumkov Center (Ukraine).

![]()

- TAGS :

- Russia

- Ukraine

- deterrence

- Donbas

- TOPICS :

- Conflict and peace

- Domestic affairs

- Military

- REGIONS :

- Eastern Europe

- Russia and CIS

png-1748065971.png)

jpg-1599133320.jpg)