Politicon.co

The Kremlin Towers are not our Roman Empire: divided in internal but united in external affairs

As we all know, whenever the Kremlin is mentioned, political researchers love bringing up its so-called “towers.” Some insist these towers are hopelessly divided, constantly pulling in different directions. Others claim they’re locked in a silent battle for dominance over one another. And then there are those who point out their different ways of dealing with neighboring states. Fair enough — there’s truth in all of this. But here’s the thing: in modern Russia, just like in its older version, those towers aren’t nearly as divided when it comes to foreign affairs. In fact, they’re remarkably united — and in this piece, we’ll show you exactly why.

Russia’s political system is often described through the metaphor of the “Kremlin towers” — competing elite groups clustered around presidential power. In its basic form, the theory distinguishes two main factions: the geopolitical tower, which advocates a hardline foreign policy, expanding Russia’s global influence and safeguarding national interests through strategic assertiveness; and the economic tower, focused on internal development, modernization, investment attraction, and business growth. While their agendas can conflict, the super-presidential system allows the president to leverage this rivalry, balancing priorities and integrating both perspectives into policy decisions.

The influence of each tower shifts with circumstances. Periods of heightened global tension or military confrontation tend to elevate the geopolitical tower, while economic downturns and domestic challenges strengthen the economic tower’s voice. This constant recalibration shapes Russia’s strategic direction, both at home and abroad, ensuring no single faction holds unchecked dominance. Yet, their competition operates within shared boundaries — neither faction fundamentally challenges the overarching framework of centralized presidential authority or Russia’s long-term goals in the post-Soviet space.

Beyond these two visible towers lies a third, less openly acknowledged but equally powerful structure — the propaganda tower. Its role is to broadcast and reinforce the precise narratives favored by the Kremlin’s leadership, shaping public opinion, controlling political discourse, and legitimizing the decisions made by the other towers. Through state media, orchestrated messaging, and information control, this tower ensures that the Kremlin’s chosen vision — whether geopolitical ambition or economic stability — is presented as both necessary and inevitable, creating an environment where elite competition remains invisible to the broader public but effective in consolidating state power.

In contrast to domestic politics, where factional rivalries shape decision-making, foreign relations in Russia are characterized by a high degree of centralization. Foreign policy is essentially V.Putin’s personal domain, with no faction enjoying real autonomy in this sphere. Every major international action of the past two decades — from the war in Ukraine to the intervention in Syria and the cultivation of alliances with China and Iran — has ultimately been led and approved by the president himself.

This dynamic is reinforced by a striking level of ideological convergence among the elite. Regardless of their affiliation or institutional base, Kremlin actors share several foundational assumptions: Russia must remain a great power, Western dominance must be resisted, and the political system must be shielded from external threats. Such broad consensus ensures that, even if tactical approaches vary, the strategic direction of foreign policy is rarely disputed.

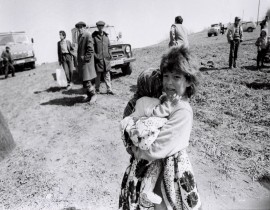

A particularly revealing element of this consensus is the perception of the post-Soviet space. Across the political spectrum inside the Kremlin, countries such as Ukraine, Belarus, South Caucasus countries and the Central Asian states are not treated as fully independent sovereign actors but as natural client states within Russia’s orbit. This attitude, rooted partly in imperial nostalgia and partly in contemporary security doctrine, drives Moscow’s recurrent interference in their domestic politics, its reliance on economic pressure to build dependency, and its use of military interventions or “peacekeeping” missions to enforce compliance.

While internal debates on foreign affairs may take place behind closed doors, they are carefully concealed from public view. Strategic discipline in messaging is a defining feature of the Kremlin’s approach: dissent on matters of foreign policy is considered a form of disloyalty, and visible unity is prioritized to project strength abroad. Moreover, the shared survival logic of the elite further narrows the scope for division. Sanctions, diplomatic isolation, and the costs of ongoing conflicts affect all factions equally, creating strong incentives to maintain cohesion. A misstep in foreign policy could endanger the entire system, and this awareness ensures that rival groups set aside their differences when it comes to Russia’s external posture.

Some researchers nevertheless point to a certain duality in international policy, likening it to a “Game of Thrones” dynamic where rival towers maneuver for influence even beyond Russia’s borders. Yet despite these interpretations, Russia’s foreign relations are still best known for presenting a single voice. The system may thrive on managed pluralism domestically, but in the international arena it projects a striking unity of purpose, with Putin’s leadership ensuring that external policy remains coherent and centralized. Increasingly, today’s government is also attempting to transpose this model of unity from the foreign policy realm to the domestic sphere, seeking to cement cohesion at home in the same way it enforces discipline abroad. This drive reflects an effort to suppress the open factionalism that once characterized the Kremlin’s inner workings, consolidating not only Russia’s international stance but also its internal political order.

In conclusion, this shift carries profound consequences for Russia’s neighbors. Given the turbulence of the current global order, the Kremlin Towers ideology itself is evolving rapidly. Where once the focus of rivalry was internal or directed toward the post-Soviet periphery, Russia’s primary targets have become international actors building their presence on the world stage. The unsettling reality for surrounding states and global powers alike is that the Kremlin’s next steps appear nearly impossible to predict. At the same time, one can argue they are not entirely unknowable: by looking closely at Russia’s historical behavior — its recurring reliance on coercion, spheres of influence, and power projection — it becomes possible to anticipate certain directions. What remains consistent, however, is that every decision — regardless of its origin in competing factions or external pressures — is ultimately signed off and confirmed by the head of state. This centralization ensures coherence, but it also injects volatility, as the calculations of one man now define the trajectory of Russia’s foreign policy, which led to the fact that the 20s years of 21st century are owned by individual politics.

Note: This article was prepared within the framework of the Politicon writing competition.

![]()

- TAGS :

jpg-1599133320.jpg)