Politicon.co

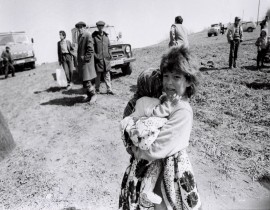

Crimean Tatars after Russian annexation

The 2014 annexation of Crimea by Russia influenced not only geopolitics and international law, but also the lives of local people, most of all, the Crimean Tatars, the indigenous population of the peninsula. In this interview Prof. Natalya Belitser whose area of expertise includes issues of interethnic relations, minorities and indigenous peoples’ rights discussed the post-2014 situation of the Crimean Tatars.

How is the current situation of Crimean Tatars after the Russian annexation? What is the policy of the Russian government towards them and how do the present Russian authorities treat them?

The current situation of Crimean Tatars after the occupation and immediately following annexation of the Crimean peninsula by Russia can be characterized as a matter of grave concern. Thousands of Crimean Tatars, especially socially and politically active, were compelled to leave their homeland, moving to the mainland Ukraine. Those who remained are under constant threat of persecutions and repressions, including illegal searches, unsubstantiated detentions, arrests, court trials charging them of violating both administrative and criminal codes, the so-called ‘disappearances’ that have been never properly investigated, tortures and even murders. At the same time, Russian policies towards the main indigenous people of the occupied peninsula are a kind of a two-track: there are insistent attempts to support and promote several traitors and collaborators while intimidating all others in order to suppress any signs of resistance to the occupation, whatever silent and peaceful. Especially vulnerable turned out to be Crimean Muslims – predominantly Crimean Tatars – who have been arrested and charged as belonging to or ‘organising a cell of Hizb-ut-Tahrir, pan-Islamic organization defined by the Russian legislation as ‘terrorist’ one (without any evidence of any wrong-doings perpetrated by the victims).

Since the invasion of Crimea by Tsarist Russia in the 18th century, Turkey has always been seen as an ally or protector of the Crimean Tatars. How can the recent Turkish-Russian rapprochement influence the situation of the Crimean Tatars?

Although this country did not join international sanctions regime following Crimea’s illegal occupation and ‘attempted annexation’, Turkey never recognised them as a fact accompli and always emphasised its support for Ukraine’s territorial integrity and sovereignty – despite all the turns of the complicated history of Russia-Turkey relations. In a number of statements and interviews, Foreign Ministry and other governmental agencies condemned persecutions and repressions taking place in the occupied Crimea, in particular, targeting Crimean Tatars and their main body of self-government – the Mejlis of Crimean Tatar people (banned according to Russian legislation as an ‘extremist organisation’).

It should also be recalled that the first unofficial mission to Crimea, aimed at studying the actual human rights situation there, especially that of Crimean Tatars, was the one from Turkey (April 26-30, 2015). Before coming to Crimea, members of the delegation had met with the leading figures of the Mejlis in Kyiv, and then with the de facto Crimean authorities, de facto Crimean Ombudsperson, representatives of the Mejlis, the Office of the Mufti of Crimea, media organizations, educational institutions and ordinary Crimean Tatars. All moves of the delegations’ members were seemingly controlled by the Crimean ‘authorities’ who tried to accompany them everywhere. Nevertheless, the report titled "The Situation of Crimean Tatars since the Annexation of Crimea by the Russian Federation" prepared by the Turkish delegation revealed the grave human rights violations against Crimean Tatars since March 2014. The report highlights that the occupational ‘government’ has intensified the repression on the Crimean Tatars, pursuing also a policy of isolation and discrediting prominent figures of the Crimean Tatar people and the members of the Mejlis. It noted a serious decline in the exercise of fundamental rights and freedoms after the annexation, like the right to assembly and demonstration as well as the freedom of expression. The report also mentions retrospective prosecutions related to the incidents taking place before the annexation, observing that the Russian laws on extremism, separatism, and terrorism were used after 18 March 2014 by the de facto government as a way to subdue all parties opposed to them in Crimea, especially the Crimean Tatars. During its visit to Crimea, the delegation noticed that feelings of fear, uncertainty and mistrust prevail among the Crimean Tatars.

It should also be noted that after the occupation, 43 Crimean Tatar NGOs of Turkey formed a united platform that has played an important role and influenced Turkish policy towards Crimea and the Crimean Tatars. Therefore, no wonder that the II World Congress of Crimean Tatars took place in Ankara (1 – 2 August 2015). 180 Crimean Tatar NGOs from 12 countries participated in the event, as well as diplomats, academics, journalists and public figures from the EU, the U.S., and Canada, whereas most delegates from Crimea were prevented from coming by obstacles created by local officials.

Overt support by Turkey of the Crimean Tatars on the occupied peninsula infuriated Moscow, especially during the acute deterioration of the Russia-Turkey relations after shooting down of a Russian plane over the Syrian-Turkish border. After restoration of ‘friendly’ relations with Turkey in 2016, there were some hopes in Russia and Crimea that it would be possible to persuade Turkey to accept Russian jurisdiction over Crimea. However, no sign of such intentions on the Turkish side is evident, and the endeavours applied by the pro-Russian political forces and organisations in both countries turned out futile. At the same time, the Turkish-Russian rapprochement might have played a decisive role in such an extraordinary event as liberation on 25 October 2017 of Akhtem Chiygoz and Ilmi Umerov – the two leaders, deputies of the Head of the Mejlis Refat Chubarov, earlier convicted in Crimea. Although no details and/or legal basis of their release have become available, there is no doubt that this decision resulted from a deal between the two Presidents – Putin and Erdoğan.

It should also be kept in mind that the electoral support of the abundant Crimean Tatars diaspora in Turkey is very important for the Turkish incumbent President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan, and that the outstanding leaders of Crimean Tatars – first and foremost, legendary Mustafa Djemilev – have always enjoyed the greatest respect and acknowledgement shared by Turkish government and society at large.

What issues are standing in the present agenda of the Crimean Tatars? What are their goals and what do they do to accomplish them?

The main goal of the Crimean Tatars from the very beginning of their repatriation from the places of exile was realisation of their right for self-determination on their homeland; this goal was strictly formulated by the Second Kurultai of the Crimean Tatar people taking place in Simferopol in June 1991 (still in the Soviet Union). During the whole period of Ukraine’s independence declared on August 24, 1991, Crimean Tatars asserted that they are not a ’national minority’ but a people, a nation, struggling to get a status of indigenous people possessing appropriate collective rights. An important issue at stake in this peaceful but insistent struggle was the existence of the democratically elected representative bodies – Kurultaj and Mejlis – that have a legitimate right to speak on behalf of the whole people. Unfortunately, this struggle had been unsuccessful until 2014 when occupation and annexation of Crimea has occurred.

These tragic events caught completely unprepared Ukraine’s interim government and society at large (as well as the international community). The alarmingly vulnerable situation of Ukraine prevented timely elaboration of any coherent strategy in dealing with the occupied territory and its own citizens remaining there. The only decisive step taken by the Verkhovna Rada, Ukrainian Parliament, was the adoption on 20 March 2014 of the Decree that recognised, eventually, the Crimean Tatars as the indigenous people of Ukraine and Mejlis and Kurultay as their main organs of self-government. This document also stressed Ukraine’s joining the UN Declaration on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples; on May 22, 2014, at the 13th sitting of the UN Permanent Forum of the indigenous peoples Ukrainian delegation in its statement asked to recognise Ukraine as a state that officially supports the Declaration and shares views and approaches stipulated by the document.

But the most important legislative steps – yet to occur – are the adoption by the Verkhovna Rada the two draft laws concerning indigenous peoples. One of them is a framework document named “On indigenous peoples of Ukraine”, defining as such Crimean Tatars, Karaits, and Krymchaks, in full compliance with the UN Declaration on the rights of indigenous peoples. The second one, “On the status of the Crimean Tatar people as an indigenous people of Ukraine”, elaborates in much more detail the means and mechanisms of safeguarding political, economic and cultural rights of the Crimean Tatars, such as functioning of their representative bodies and their interaction with national and regional authorities and organs of self-government and defines quotas of Crimean Tatars representatives in the elected bodies, and in general, provides firm guarantees for their efficient participation in the political decision-making processes. Article 1 of this draft law provides the following definition: “The indigenous Crimean Tatar people is an integral ethnos which formed at the territory of the Crimean peninsula, which preserved and wishes to transit to the next generations its collective ethnocultural identity, is a bearer of its own native language and culture, has had traditional social, cultural, and political institutions, has formed the well-developed system of self-governance, self-identifies as an indigenous people of Ukraine, and has no statehood of its own or ethnically related state beyond the borders of Ukraine”.

Although not all of the Crimean Tatars leaders and activists fully share such an approach – some would prefer more radical steps stressing actually the restoration of their statehood lost after the first annexation of the Crimea by the Russian Empire in 1783 – in general, successful realisation of such a policy would signify that Ukraine eventually has met Crimean Tatars’ goals and aspirations. This vision is also an essential component of a more comprehensive strategy of the de-occupation of Crimea.

![]()

- TAGS :

- Russia

- Ukraine

- Crimea

- Crimean Tatars

- Turkey

- REGIONS :

- Eastern Europe

- Russia and CIS

jpg-1599133320.jpg)